Summary: The concept has never been well understood. What should be clear, however, is that the president lacks the authority to declare it.

Published: August 20, 2020

On August 20, 1942, military police in Honolulu, Hawaii, arrested a man named Harry White. Under normal circumstances, the U.S. military would not have been involved in his case. He was a stockbroker, not a soldier, and neither he nor his business had any connection with the armed forces. Even his alleged crime — embezzlement of funds from a client — was a violation of civilian, not military, law. footnote1_mLzIhiMJjHnh 1 Duncan v. Kahanamoku, 327 U.S. 304, 309–10 (1946).

But nothing about Hawaii was normal in 1942. It had been under martial law since the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. footnote2_s5fco5FauyaE 2 Although Hawaii was an incorporated territory, not a state, in 1942, the Supreme Court found that the Constitution applied there in full and that the legality of martial law must be analyzed as though it were a state. Duncan, 327 U.S. at 319. Its courts were closed and replaced with military tribunals. The rules governing everyday life were set not by an elected legislature but by the military governor. The army controlled every aspect of life in the islands, from criminal justice to parking zones and curbside trash removal. footnote3_c7uo9RbAy2zf 3 Harry N. Scheiber and Jane L. Scheiber, Bayonets in Paradise: Martial Law in Hawai’i during World War II (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2016).

White was brought before a military provost court. His attorney objected to the court’s jurisdiction, requested a jury trial, and asked for time to prepare a defense. But Major Murrell, the presiding military officer, rejected these motions. Instead, just five days after being arrested, White was tried without a jury, convicted, and sentenced to five years in prison. footnote4_ef4ue76ucBwy 4 Duncan, 327 U.S. at 309–10; and Ex parte Duncan, 146 F.2d 576, 577 (9th Cir. 1945).

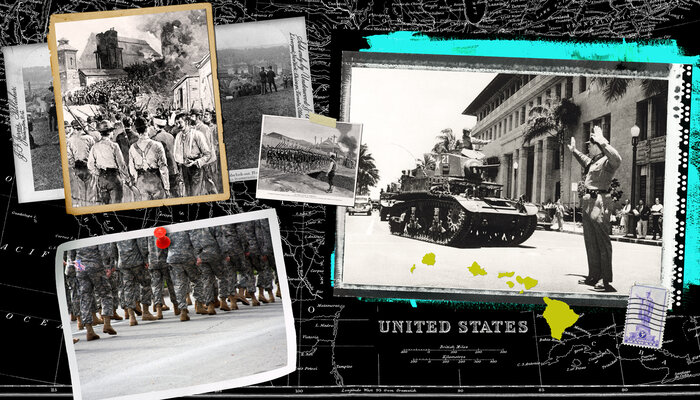

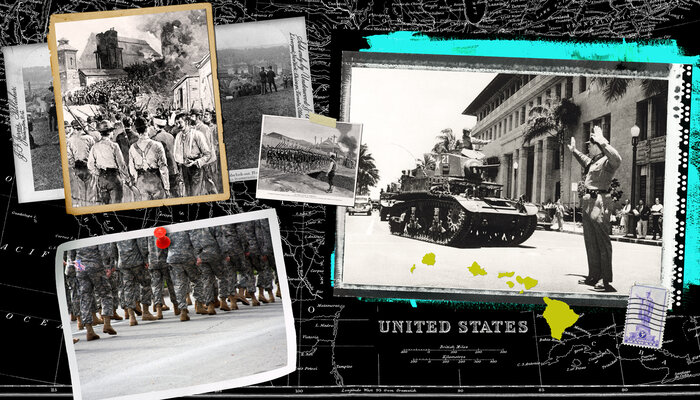

As White’s story illustrates, martial law — a term that generally refers to the displacement of civilian authorities by the military — can be and has been employed in the United States. Indeed, federal and state officials have declared martial law at least 68 times over the course of U.S. history. footnote5_skDELhfX7A5S 5 Joseph Nunn, Guide to Declarations of Martial Law in the United States, Brennan Center for Justice, August 20, 2020, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/guide-declarations-martial-law-united-states. Yet the concept has never been well understood. The Constitution does not mention martial law, and no act of Congress defines it. The Supreme Court has addressed it on only a handful of occasions, and the Court’s reasoning in these decisions is inconsistent and vague. footnote6_jqetVdLEJ0AM 6 Duncan, 327 U.S. 304; Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U.S. 378 (1932); Moyer v. Peabody, 212 U.S. 78 (1909); Ex parte Milligan, 71 U.S. 2 (1866); and Luther v. Borden, 48 U.S. 1 (1849). The precedents are also old: the most recent one — in which the Court overturned Harry White’s conviction — was decided almost 75 years ago.

This report aims to clear up the confusion that surrounds martial law. To do so, it draws on recent legal scholarship, the few rules that can be gleaned from Supreme Court precedent, and general principles of constitutional law. It concludes that under current law, the president lacks any authority to declare martial law. Congress might be able to authorize a presidential declaration of martial law, but this has not been conclusively decided. State officials do have the power to declare martial law, but their actions under the declaration must abide by the U.S. Constitution and are subject to review in federal court.

Outside of these general principles, there are many questions that simply cannot be answered given the sparse and confusing legal precedent. Moreover, although lacking authority to replace civilian authorities with federal troops, the president has ample authority under current law to deploy troops to assist civilian law enforcement. Until Congress and state legislatures enact stricter and better-defined limits, the exact scope of martial law will remain unsettled, and the president’s ability to order domestic troop deployments short of martial law will be dangerously broad.

Although Hawaii was an incorporated territory, not a state, in 1942, the Supreme Court found that the Constitution applied there in full and that the legality of martial law must be analyzed as though it were a state. Duncan, 327 U.S. at 319.

Harry N. Scheiber and Jane L. Scheiber, Bayonets in Paradise: Martial Law in Hawai’i during World War II (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2016).

Joseph Nunn, Guide to Declarations of Martial Law in the United States, Brennan Center for Justice, August 20, 2020, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/guide-declarations-martial-law-united-states.

Duncan, 327 U.S. 304; Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U.S. 378 (1932); Moyer v. Peabody, 212 U.S. 78 (1909); Ex parte Milligan, 71 U.S. 2 (1866); and Luther v. Borden, 48 U.S. 1 (1849).

“Martial law” has no established definition. footnote1_oymfQ1ZjDpjn 1 Duncan, 327 U.S. at 315 (“The term martial law carries no precise meaning.”).

In the United States, however, the military’s domestic activities typically fall into one of three categories. First, the armed forces sometimes assist civilian authorities with “non–law enforcement” functions. For example, in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the military deployed helicopters along the Gulf Coast to carry out search-and-rescue missions that local governments were unable to do themselves. Second, and far less frequently, the military assists civilian authorities with “law enforcement” activities. For example, state and federal troops were deployed to help police suppress the 1992 Los Angeles riots. Third, on some occasions, the military has taken the place of the civilian government. This is what happened in Hawaii during World War II.

Usually, but not always, the term “martial law” refers to the third category. It describes a power that, in an emergency, allows the military to push aside civilian authorities and exercise jurisdiction over the population of a particular area. Laws are enforced by soldiers rather than local police. Policy decisions are made by military officers rather than elected officials. People accused of crimes are brought before military tribunals rather than ordinary civilian courts. In short, the military is in charge. footnote2_ewdW5m75CsCo 2 William C. Banks and Stephen Dycus, Soldiers on the Home Front:The Domestic Role of the American Military (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016), 198; John Fabian Witt, “A Lost Theory of American Emergency Constitutionalism,” Law and History Review 36 (August 2018): 581–83; Stephen I. Vladeck, “The Field Theory: Martial Law, the Suspension Power, and the Insurrection Act,” Temple Law Review 80 (Summer 2007): 391–439; Stephen I. Vladeck, “Emergency Power and the Militia Acts,” Yale Law Journal 114 (Fall 2004): 149, 162; and George M. Dennison, “Martial Law: The Development of a Theory of Emergency Powers, 1776–1861,” American Journal of Legal History 18 (January 1974): 61.

This is a dramatic departure from normal practice in the United States. The U.S. military, when allowed to act domestically at all, is ordinarily limited to assisting civilian authorities. Martial law turns that relationship on its head. The displacement of civilian government distinguishes it from other emergency powers, such as the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. Suspending the writ allows the government to detain and hold individuals without charge but does not imply any unusual role for the armed forces. While a declaration of martial law might be accompanied by a suspension of habeas corpus, they are distinct concepts.

Martial law has not always meant what it does today. The term first appeared in England in the 1530s during the reign of King Henry VIII. footnote3_jHwKjS4GZ6ID 3 John M. Collins, Martial Law and English Laws, c. 1500–c. 1700 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 27. At that time and for centuries afterward, martial law generally referred to what is now called “military law.” footnote4_nUol1NGAjwmx 4 Collins, Martial Law and English Laws, 3–7; and Dennison, “Martial Law,” 52. This is the law that applies when a soldier is court-martialed. In the modern United States, it is codified in the Uniform Code of Military Justice. footnote5_qLRubttojas0 5 Uniform Code of Military Justice, 64 Stat. 109, 10 U.S.C. §§ 801–946.

U.S. law did not recognize martial law as an emergency power until the mid-19th century. Before that time, the idea of allowing military rule in an emergency was considered outrageous — as evidenced by the national reaction to the first declaration of martial law in U.S. history. In December 1814, toward the end of the War of 1812, Gen. Andrew Jackson led a small army in the defense of New Orleans against a much larger invading British force. As part of his defensive preparations, Jackson imposed martial law on the city. He censored the press, enforced a curfew, and detained numerous civilians without charge. Moreover, he continued military rule for more than two months after his famous victory at the Battle of New Orleans had ended any real threat from the British. footnote6_nAAtbo9297Iw 6 Matthew Warshauer, Andrew Jackson and the Politics of Martial Law: Nationalism, Civil Liberties, and Partisanship (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), 19–46.

Jackson argued that his actions were justified because the government in New Orleans had ceased to function as a result of the impending British attack, leaving the military as the only body able to protect the city. In that situation, he claimed, the military had the authority to do anything that was “necessary” to preserve New Orleans. footnote7_jMLWrH2Zf5lN 7 Dennison, “Martial Law,” 61–62; and Vladeck, “Field Theory,” 422. This was a novel argument, and it did little to explain why he kept the city under martial law for so long.

At the time, almost everyone rejected Jackson’s theory, which perhaps is unsurprising. The founding generation had been deeply suspicious of military power. That suspicion is apparent in the Declaration of Independence, which accuses King George III of rendering “the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power” — and in the Constitution, which pointedly divides the war powers between Congress and the president, and requires that the commander in chief always be a civilian. footnote8_fNrbK1giiWGF 8 Vladeck, “Emergency Power and the Militia Acts,” 156–58.

In an 1815 case, the Louisiana Supreme Court described Jackson’s conduct in New Orleans as “trampling upon the Constitution and laws of our country.” footnote9_k0DSmq7EkNCA 9 Dennison, “Martial Law,” 64 (citing Johnson v. Duncan et al. Syndics, 1 Harr. Cond. Rep. 157–70 [1815]). Similarly, acting Secretary of War Alexander Dallas explained in a letter to Jackson that martial law had no legal existence in the United States outside of the Articles of War, the predecessor to the modern Uniform Code of Military Justice. footnote10_e7DipwSH3Nax 10 Dennison, “Martial Law,” 64 (citing Dallas to Jackson, 12 April, 1 July 1815, in John Spencer Bassett and J. Franklin Jameson, eds., Correspondence of Andrew Jackson, vol. 2, Andrew Jackson Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 1926–35, 203–4, 212–13). Overall, the consensus in 1815 was that martial law was simply another term for military law, and that military jurisdiction could extend no further than the armed forces themselves.

After Jackson relinquished control of New Orleans back to its civilian government, the local federal district judge held him in contempt of court, fining him $1,000. Jackson paid the fine, and for the next 27 years, nothing more came of the incident. However, in the early 1840s, the now-aging former president orchestrated a campaign in Congress to refund him the cost of the fine, plus interest. footnote11_lyjc1MiqZOKX 11 Warshauer, Andrew Jackson and the Politics of Martial Law, 6–12.

The ensuing congressional refund debates marked the beginning of a shift in how Americans understood martial law. By pursuing a refund, Jackson hoped to set a precedent for, as one historian put it, “the legitimacy of violating the Constitution and civil liberties in times of national emergency.” footnote12_dyYgBjuEcoY1 12 Warshauer, Andrew Jackson and the Politics of Martial Law, 5–6. He got exactly what he wanted. Congress enacted the refund bill in February 1844, symbolically endorsing Jackson’s three-month-long imposition of martial law in New Orleans almost 30 years after it had ended. footnote13_qzuY9tDqBwFg 13 Act of February 16, 1844, ch. 2, 5 Stat. 651.

By this time, the United States’ second experience with martial law was already underway in Rhode Island. The so-called “Dorr War” involved a dispute over the state’s first constitution, which severely restricted the right to vote. In 1842, after efforts to reform this system had been rebuffed for years, a large group of Rhode Islanders led by Thomas Dorr organized its own constitutional convention, adopted a new constitution, held elections, and declared itself the true government of Rhode Island. When Dorr rallied his supporters to assert their authority by force, the Rhode Island General Assembly declared martial law and called out the state militia to suppress the rebellion. footnote14_r8lZlRyQt7ft 14 Luther, 48 U.S. at 35–37; and Dennison, “Martial Law,” 68.

In 1849, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the legality of Rhode Island’s martial law declaration in Luther v. Borden. footnote15_vzhMkk0iiH8R 15 Luther, 48 U.S. at 47.

Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Roger Taney — of Dred Scott infamy — embraced Andrew Jackson’s idea that martial law allows civilians to be subjected to military jurisdiction in an emergency. He described this power as an essential part of states’ right to defend themselves and suggested that it is inherent to all sovereign governments. footnote16_ttvUGbwlmtZ8 16 Luther, 48 U.S. at 45. By endorsing the constitutionality of martial law, the Supreme Court finished what Congress had started with the refund bill. The Luther decision makes clear that martial law exists as an emergency power that can be invoked in the United States, at least by state legislatures. footnote17_oegYGK0LlJY7 17 Vladeck, “Field Theory,” 428–29; and Dennison, “Martial Law,” 76.

But Luther also leaves many questions unanswered. It does not explain the legal basis for martial law, its scope, when it may be declared, or who is authorized to declare it. Indeed, the Supreme Court has never directly held, in Luther or any subsequent case, that the federal government has the power to impose martial law. In one case, the Court suggested in “dicta”— a term for language in a judicial opinion that is not a necessary part of the holding and is not strictly legally binding — that the federal government may declare martial law. footnote18_aYE72PyVxdUI 18 Milligan, 71 U.S. at 127. It assumed the same in another case, but only for the purpose of deciding a narrower legal question. footnote19_j45vBAIE5kVi 19 Duncan, 327 U.S. at 313. Neither of those decisions conclusively affirms that a federal martial law power exists.

Indeed, the Supreme Court has never directly held, in Luther or any subsequent case, that the federal government has the power to impose martial law.

Over time, however, consistency of practice has papered over gaps in the legal theory. The United States made extensive use of martial law during the Civil War, imposing it on border states like Missouri and Kentucky where U.S. forces battled with Confederate insurgents. footnote20_bV4PsPwbbLQB 20 Vladeck, “Emergency Power and the Militia Acts,” 175–83; and Banks and Dycus, Soldiers on the Home Front, 203–7. The Confederacy, too, relied on it heavily. footnote21_fTBbIzCsv7gf 21 Mark E. Neely Jr., Southern Rights: Political Prisoners and the Myth of Confederate Constitutionalism (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999). The practice did not end with the war: in the 90 years between the start of the Civil War and the end of World War II, martial law was declared at least 60 times. footnote22_zuKK2VUg8b7G 22 Joseph Nunn, Guide to Declarations of Martial Law in the United States, Brennan Center for Justice, August 20, 2020. What had been manifestly unconstitutional in the eyes of the Louisiana Supreme Court in 1815 had become a relatively ordinary part of American life by the end of the 19th century.

States — and state governors in particular — have declared martial law far more often than the federal government. In the 1930s, Oklahoma Governor William “Alfalfa Bill” Murray declared martial law at least 6 and perhaps more than 30 times during his tenure. footnote23_bhuC5PqiAsiS 23 Debbie Jackson and Hilary Pittman, “Throwback Tulsa: Colorful ‘Alfalfa Bill’ Fell Short in Presidential Bid,” Tulsa World, July 14, 2016, https://www.tulsaworld.com/news/local/history/throwback-tulsa-colorful-alfalfa-bill-fell-short-in-presidential-bid/article_23b7bd2f-12ce-5415-a92f-937ecb40c0a6.html. City mayors and generals within states’ National Guard forces have also declared martial law on occasion. However, no state legislature has done so since the Rhode Island General Assembly in 1842.

Not all of the military deployments under these declarations included what we today consider the defining feature of “martial law” — the displacement of civilian authority. Many cases involved the use of the military to reinforce local police. In other cases, however, troops effectively replaced the police, and in some instances, they were used to impose the will of state or local officials rather than to enforce the law.

State officials have sometimes declared martial law in response to violent civil unrest or natural disasters, such as the Akron Riot of 1900 or the 1900 Galveston hurricane. footnote24_bgpt60GMjil5 24 Mary Plazo, “That Akron Riot,” Past Pursuits: A Newsletter of the Special Collections Division of the Akron-Summit County Public Library 9 (Summer 2010): 7, https://www.akronlibrary.org/images/Divisions/SpecCol/images/PastPursuits/pursuits92.pdf; and “Martial Law at an End: Conditions at Galveston Improving,” Los Angeles Herald, September 21, 1900, 2. Far more often, however, they have used martial law to break labor strikes on behalf of business interests. For example, in September 1903, at the request of mine owners, Colorado Governor James Peabody declared martial law in Cripple Creek and Telluride to break a peaceful strike by the Western Federation of Miners. The Colorado National Guard conducted mass arrests of striking workers and detained them in open-air bull pens. The Guard even ignored state court orders to release the prisoners, with one officer declaring, “To hell with the constitution.” footnote25_qJMS04wWbjZf 25 Elizabeth Jameson, All That Glitters—Class, Conflict, and Community in Cripple Creek (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 207–8.

States’ use of martial law continued well into the 20th century, reaching a peak in the 1930s — a decade that also saw an increase in the flagrant abuse of this power by governors. In 1933, for example, Georgia Governor Eugene Talmadge declared martial law “in and around” the headquarters building of the state Highway Board as part of a scheme to force out some of the board’s commissioners, whom he had no legal power to remove. This “coup de highway department” was ultimately successful. Remarkably, Talmadge’s successor, Governor Eurith Rivers, tried to do the same thing in 1939, but his attempt failed. footnote26_g7zMmTd6CpEv 26 “National Affairs: Martial Law,” Time, July 3, 1933, http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,745726,00.html; and Miller v. Rivers, 31 F. Supp. 540 (M.D. Ga. 1940), rev’d as moot, 112 F.2d 439 (5th Cir. 1940).

Misuses of martial law were not confined to Georgia. In 1931, Texas Governor Ross Sterling engaged in a standoff with the federal courts over his government’s ability to enforce a regulation limiting oil production by private well operators. At the climax of the conflict, Sterling imposed martial law on several counties — despite the total absence of violence or threats of violence — and deployed the Texas National Guard to enforce the regulation. He declared that the federal courts had no power to review his decision. The U.S. Supreme Court disagreed, explaining that “[t]here is no such avenue of escape from the paramount authority of the Federal Constitution.” footnote27_bhEl8LEKhOmI 27 Sterling, 287 U.S. at 398, 403–4. It ordered Texas to stop using the military or any other means to enforce the regulation.

The federal government has used martial law far less frequently than the states, imposing it only a few times since the end of Reconstruction. Generals have declared it more often than the president, such as in 1920, when U.S. Army Gen. Francis C. Marshall imposed martial law on Lexington, Kentucky, in order to suppress a lynch mob attempting to storm the courthouse. footnote28_dGVC4vmFsnz8 28 Peter Brackney, The Murder of Geneva Hardman and Lexington’s Mob Riot of 1920 (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2020), 97–98. Most recently, the federal government declared martial law in Hawaii after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, which initiated three years of absolute military rule in the islands. footnote29_qSX2cRgdfYXn 29 Scheiber and Scheiber, Bayonets in Paradise.

As abruptly as it took hold in the mid-19 th century, martial law disappeared from American life after World War II. The federal government has not declared martial law since it restored civilian rule to Hawaii in 1944. At the state level, martial law was last declared in 1963, when Maryland Governor J. Millard Tawes imposed it on the city of Cambridge for more than a year in response to clashes between racial justice advocates and segregationists. footnote30_t7gL6iK2SLdB 30 Joseph R. Fitzgerald, The Struggle Is Eternal: Gloria Richardson and Black Liberation (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2018), 121–29; Rebecca Contreras, “Cambridge, Maryland, Activists Campaign for Desegregation, USA, 1962–1963,” Global Nonviolent Action Database, last modified July 27, 2011, accessed July 30, 2020, https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/cambridge-maryland-activists-campaign-desegregation-usa-1962–1963; Hedrick Smith, “Martial Law Is Imposed in Cambridge, Md., Riots,” New York Times, July 13, 1963, 1, 6, https://nyti.ms/30fTf3i; and “Tawes Withdraws Last Guard Troops in Cambridge, Md.,” New York Times, July 8, 1964, 18, https://nyti.ms/39PfcK0 . But even if the power to declare martial law has not been used in decades, it still exists in the case law and in the record books — and it remains poorly understood.

William C. Banks and Stephen Dycus, Soldiers on the Home Front: The Domestic Role of the American Military (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016), 198; John Fabian Witt, “A Lost Theory of American Emergency Constitutionalism,” Law and History Review 36 (August 2018): 581–83; Stephen I. Vladeck, “The Field Theory: Martial Law, the Suspension Power, and the Insurrection Act,” Temple Law Review 80 (Summer 2007): 391–439; Stephen I. Vladeck, “Emergency Power and the Militia Acts,” Yale Law Journal 114 (Fall 2004): 149, 162; and George M. Dennison, “Martial Law: The Development of a Theory of Emergency Powers, 1776–1861,” American Journal of Legal History 18 (January 1974): 61.

John M. Collins, Martial Law and English Laws, c. 1500–c. 1700 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 27.

Matthew Warshauer, Andrew Jackson and the Politics of Martial Law: Nationalism, Civil Liberties, and Partisanship (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), 19–46.

Dennison, “Martial Law,” 64 (citing Johnson v. Duncan et al. Syndics, 1 Harr. Cond. Rep. 157–70 [1815]).

Dennison, “Martial Law,” 64 (citing Dallas to Jackson, 12 April, 1 July 1815, in John Spencer Bassett and J. Franklin Jameson, eds., Correspondence of Andrew Jackson, vol. 2, Andrew Jackson Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 1926–35, 203–4, 212–13).

Vladeck, “Emergency Power and the Militia Acts,” 175–83; and Banks and Dycus, Soldiers on the Home Front, 203–7.

Mark E. Neely Jr., Southern Rights: Political Prisoners and the Myth of Confederate Constitutionalism (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999).

Joseph Nunn, Guide to Declarations of Martial Law in the United States, Brennan Center for Justice, August 20, 2020.

Debbie Jackson and Hilary Pittman, “Throwback Tulsa: Colorful ‘Alfalfa Bill’ Fell Short in Presidential Bid,” Tulsa World, July 14, 2016, https://www.tulsaworld.com/news/local/history/throwback-tulsa-colorful-alfalfa-bill-fell-short-in-presidential-bid/article_23b7bd2f-12ce-5415-a92f-937ecb40c0a6.html.

Mary Plazo, “That Akron Riot,” Past Pursuits: A Newsletter of the Special Collections Division of the Akron-Summit County Public Library 9 (Summer 2010): 7, https://www.akronlibrary.org/images/Divisions/SpecCol/images/PastPursuits/pursuits92.pdf; and “Martial Law at an End: Conditions at Galveston Improving,” Los Angeles Herald, September 21, 1900, 2.

Elizabeth Jameson, All That Glitters—Class, Conflict, and Community in Cripple Creek (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 207–8.

“National Affairs: Martial Law,” Time, July 3, 1933, http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,745726,00.html; and Miller v. Rivers, 31 F. Supp. 540 (M.D. Ga. 1940), rev’d as moot, 112 F.2d 439 (5th Cir. 1940).

Peter Brackney, The Murder of Geneva Hardman and Lexington’s Mob Riot of 1920 (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2020), 97–98.

Joseph R. Fitzgerald, The Struggle Is Eternal: Gloria Richardson and Black Liberation (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2018), 121–29; Rebecca Contreras, “Cambridge, Maryland, Activists Campaign for Desegregation, USA, 1962–1963,” Global Nonviolent Action Database, last modified July 27, 2011, accessed July 30, 2020, https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/cambridge-maryland-activists-campaign-desegregation-usa-1962–1963; Hedrick Smith, “Martial Law Is Imposed in Cambridge, Md., Riots,” New York Times, July 13, 1963, 1, 6, https://nyti.ms/30fTf3i; and “Tawes Withdraws Last Guard Troops in Cambridge, Md.,” New York Times, July 8, 1964, 18, https://nyti.ms/39PfcK0 .

Despite the widespread use of martial law in the century that followed the Supreme Court’s ruling in Luther, many of the legal questions surrounding it remain unanswered. The Court has never explained the legal basis for martial law. It has implied that the federal government can declare it but has never said so conclusively. When discussing the possibility of a federal martial law power, the Court has never clearly indicated whether the president could unilaterally declare martial law or if Congress would first need to authorize it.

Insofar as the Supreme Court has said anything on these questions, its statements have been inconsistent. During the 19th century, the Court suggested in dicta that a federal martial law power was “implied in sovereignty” or justified by “necessity.” footnote1_tSVBGVbXOXv7 1 Luther, 48 U.S. at 45; and United States v. Diekelman, 92 U.S. 520, 526 (1875). In the early 20th century, it seemed to believe that the state martial law power was related to the executive’s constitutional power to “execute the law.” footnote2_flYNiSLPM5hW 2 Sterling, 287 U.S. at 398; and Duncan, 327 U.S. at 335 (Stone, C. J., concurring in the result). Note that both the portion of Luther that Chief Justice Stone cites and the rest of his opinion directly contradict his own opening proposition. During World War II, the Court assumed (without deciding) that Congress could authorize a federal declaration of martial law but did not make clear whether that authorization was required. footnote3_mll1QkHMrrVz 3 Duncan, 327 U.S. at 312–24. In contrast, in a much earlier but influential 1866 concurring opinion, Chief Justice Salmon Chase did conclude that federal martial law exists and that it must be authorized by Congress. footnote4_sRC7qQ6zVsjm 4 Milligan, 71 U.S. at 132–42 (Chase, C. J., concurring in part and dissenting in part).

Looking only at the Supreme Court’s martial law decisions, one can pick and choose from them to argue for almost anything. The case law is inconsistent and too sparse for a clear pattern in the Court’s reasoning to emerge. It is also old: even the most recent Supreme Court decision on martial law — Duncan v. Kahanamoku, decided in 1946 — predates many significant developments in U.S. constitutional law. footnote5_r8LsiNVoyYg0 5 Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952); Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961); Massiah v. United States, 377 U.S. 201 (1964); Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965); Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966); Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 542 U.S. 507 (2004); Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, 548 U.S. 557 (2006); Boumediene v. Bush, 553 U.S. 723 (2008); and War Powers Resolution, 50 U.S.C. §§ 1541–48. The precedents thus provide little help in determining the legal basis for martial law — or, assuming that federal martial law is even permissible, whether its use is controlled by Congress or the president.

Under Youngstown, the courts show varying degrees of deference to presidential action, depending on whether the president is acting in accordance with or contrary to the will of Congress. Justice Jackson identified three “zones” into which presidential actions might fall. In the first zone, Congress has authorized the president’s conduct, entitling it to maximum deference from the courts. The court will uphold the action unless the federal government, as a whole, lacks the power to act. In the second zone, Congress has said nothing on the matter, so courts must search the Constitution to find some independent authority for the president’s action. In the third zone, the president’s conduct is contrary to laws Congress has passed. These actions are impermissible unless Congress has overstepped its own powers. footnote8_a90zJrUo5Dub 8 Youngstown, 343 U.S. at 635–38 (Jackson, J., concurring).

Although Youngstown did not address a declaration of martial law, Justice Jackson’s concurring opinion briefly mentioned the concept. Having stated that the Constitution’s drafters “made no express provision for exercise of extraordinary authority because of a crisis,” he included the following caveat in a footnote: “I exclude, as in a very limited category by itself, the establishment of martial law.” footnote9_nU25hBo7zVS5 9 Youngstown, 343 U.S. at 650n19 (Jackson, J., concurring). This language acknowledges the possibility that martial law might exist as an emergency power, despite the lack of any express provision for it in the Constitution. It does not, however, suggest where that power lies, and certainly does not indicate that it belongs solely to the executive branch. Nor does it render the three-zone test inapplicable in the context of martial law.

How would a unilateral presidential declaration of martial law on the southern border fare under Youngstown’s three-zone test? We start with what Congress has said: Congress has legislated so extensively with respect to the domestic use of the military — through, for example, the Posse Comitatus Act, the Insurrection Act, the Stafford Act, the Non Detention Act, and various other provisions within Title 10 of the U.S. Code — that it has “occupied the field.” footnote10_wfRG3QEb1iSw 10 18 U.S.C. § 1385; 10 U.S.C. §§ 251–55; 42 U.S.C. § 5121 et seq.; 18 U.S.C. § 4001(a); 10 U.S.C ch. 15, §§ 271–84; and Youngstown, 343 U.S. at 639 (Jackson, J., concurring). This means that Congress has created such a dense and comprehensive network of rules that anything the president does in this area that is not affirmatively authorized by statute is almost necessarily against Congress’s will. Such actions, including a hypothetical presidential declaration of martial law that Congress has not authorized, would fall within Youngstown’s third zone.

Furthermore, the Posse Comitatus Act creates a general rule that it is unlawful for federal military forces to engage in civilian law enforcement activities — even if they are merely supplementing rather than supplanting civilian authorities — except when doing so is expressly authorized by Congress. footnote11_i26iThR0FUcC 11 Jennifer K. Elsea, The Posse Comitatus Act and Related Matters: The Use of the Military to Execute Civilian Law, CRS report no. R42659 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2018), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/R42659.pdf. The Posse Comitatus Act nominally allows for constitutional exceptions to its general rule, but none exists. As it is generally understood, martial law necessarily involves military participation in civilian law enforcement. While there are a number of statutory exceptions to the Posse Comitatus Act, none of them authorizes the president to declare martial law, as part III of this report explains. Therefore, the president’s declaration of martial law would directly violate the act, which again places it within zone 3 under Youngstown.

In zone 3, the president’s powers are at their “lowest ebb” and presidential actions are rarely upheld. footnote12_vbAKeAAyMQPN 12 Youngstown, 343 U.S. at 639 (Jackson, J., concurring). This reflects a general rule of constitutional law: that laws passed by Congress within the scope of its own constitutional powers “disable” contrary executive action. footnote13_fLumwVdP4HmL 13 Hamdan, 548 U.S. at 593n23 (“Whether or not the President has independent power, absent congressional authorization, to convene military commissions, he may not disregard limitations that Congress has, in proper exercise of its own war powers, placed on his powers.”); Youngstown, 343 U.S. at 654–55 (Jackson, J., concurring); Little v. Barreme, 6 U.S. 170 (1804); and Powell, President as Commander in Chief, 101–8. In other words, when Congress and the president disagree, Congress wins. Under Youngstown, this rule may be overcome — and the president can act against the will of Congress — only when a “conclusive and preclusive” grant of presidential power in the Constitution authorizes the challenged action. footnote14_fHN2vMejRQ5O 14 Youngstown, 343 U.S. at 637–38 (Jackson, J., concurring). If the Constitution gives Congress any powers in that area, then the president’s authority is not “conclusive and preclusive,” and Congress’s will must prevail.

The critical question, then, is how the Constitution allocates the powers related to domestic deployment of the military. Three provisions of the Constitution implicate that sort of authority: the Calling Forth Clause in Article I, the Guarantee Clause in Article IV, and the Commander in Chief Clause in Article II. footnote15_xSKOC6BrMR6e 15 U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 15 (empowering Congress “[t]o provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions.”); U.S. Const. art. IV, § 4 (“The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government, and shall protect each of them against Invasion; and on Application of the Legislature, or of the Executive (when the Legislature cannot be convened) against domestic Violence.”); and U.S. Const. art. II, § 2, cl. 1 (“The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States.”). The balance of power established by these provisions decisively favors Congress over the president.

The Calling Forth Clause empowers Congress to “provide for” — that is, to regulate and control — the authority and procedures for “calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions.” As Justice Jackson explained in Youngstown, this provision was “written at a time when the militia rather than a standing army was contemplated as the military weapon of the Republic.” footnote16_lPKamrLQHwKV 16 Youngstown, 343 U.S. at 644 (Jackson, J., concurring). It thus “underscores the Constitution’s policy that Congress, not the Executive, should control utilization of the war power as an instrument of domestic policy.” footnote17_m0KYonRFkHpA 17 Youngstown, 343 U.S. at 644 (Jackson, J., concurring); and Stephen I. Vladeck, “The Calling Forth Clause and the Domestic Commander-in-Chief,” Cardozo Law Review 29 (January 2008): 1091–108.

The Guarantee Clause requires the United States to “protect each [state] against Invasion; and on Application of the Legislature, or the Executive (when the Legislature cannot be convened) against domestic Violence.” This language is less clear-cut than the Calling Forth Clause, but it certainly does not constitute a “conclusive and preclusive” commitment of power to the executive. Instead, it grants authority to the federal government as a whole. Furthermore, it only allows unilateral federal action in the case of invasion. In the event of “domestic violence,” the affected state must request help before the federal government can act.

Lastly, the Commander in Chief Clause would not enable the president to unilaterally declare martial law in disregard of the Posse Comitatus Act and other statutes that regulate the domestic use of the military. To start, the Commander in Chief Clause is not a source of domestic regulatory authority for the president. footnote18_sZqyt1HJfkpP 18 Youngstown, 343 U.S. at 643–44 (Jackson, J., concurring); and Powell, President as Commander in Chief, 120–21. As Justice Jackson explained in Youngstown, “the Constitution did not contemplate that the title Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy” would also mean the president was “Commander-in-Chief of the country, its industries and its inhabitants.” footnote19_yV7atJhJf8cf 19 Youngstown, 343 U.S. at 643–44 (Jackson, J., concurring). While the clause grants something more than an “empty title,” its invocation does not give the president free rein. footnote20_yMcRNidJaDqY 20 Youngstown, 343 U.S. at 641 (Jackson, J., concurring). In domestic affairs, both generally and with respect to the role of the military, the Constitution envisions Congress as the branch in control. footnote21_nq8iXQMdqhGS 21 Vladeck, “Calling Forth Clause and the Domestic Commander-in-Chief,” 1106.

To be sure, the president’s powers under the Commander in Chief Clause do not cease to exist inside the territorial United States. If a foreign enemy launches a sudden attack inside the United States, it is generally understood that the president may act to repel that attack, even if Congress has not given its blessing. footnote22_sI2MFFbywLO0 22 Prize Cases, 67 U.S. (2 Black) 635, 669 (1862). And if Congress has authorized military action, the president controls the actual conduct of military operations, even if that fighting is taking place within the country’s borders (for instance, during a foreign invasion or civil war). But the former power is quite limited, and the latter relies on prior congressional authorization.

Because the Constitution does not give the president “conclusive and preclusive” authority over the domestic use of the military — and, on the contrary, explicitly vests power in the legislative branch — the president cannot act against Congress’s wishes in this area. Accordingly, a unilateral declaration of martial law by the president today — on the southern border or elsewhere — would not survive a legal challenge under Youngstown.

It bears emphasizing that this conclusion is compelled partly by the Constitution and partly by federal law. It is possible that, in the absence of the Posse Comitatus Act and other laws regulating domestic military activity, the president could rely on some independent executive power to declare martial law. But that scenario is hypothetical and the likely legal outcome is uncertain. The reality is that the domestic role of the U.S. military is subject to pervasive statutory regulation. This has altered what might otherwise be the scope of the president’s constitutional authority and precludes a unilateral presidential declaration of martial law. footnote23_zHpmdtoaQRpf 23 In Justice Jackson’s words, “presidential powers are not fixed but fluctuate, depending upon their disjunction or conjunction with those of Congress.” Youngstown, 343 U.S. at 635 (Jackson, J., concurring); and Powell, President as Commander in Chief, 99–100.

In the imagined scenario described earlier, the president set up military tribunals to try violators of federal immigration law. The Posse Comitatus Act, however, only applies to military participation in law enforcement. When it comes to military involvement in judicial functions, the analysis changes, and the law is characterized by profound uncertainty. While the Calling Forth Clause expressly contemplates the use of military forces to execute the law, no provision of the Constitution authorizes the military to perform the functions assigned to the judicial branch under Article III. Nonetheless, the Supreme Court’s 1866 decision in Ex parte Milligan suggests that the president can, in certain circumstances, impose martial law in an area and replace the civilian courts there with military tribunals. footnote24_wXYoCJDFMPw9 24 Milligan, 71 U.S. at 127.

The Court’s reasoning in Milligan has some striking inconsistencies and must be interpreted cautiously. In one part of the opinion, the Court firmly asserts that emergency conditions can never justify exceeding the bounds of the Constitution. footnote25_rOV8DnKpPAtc 25 Milligan, 71 U.S. at 120–21. Elsewhere, however, the Court says that “necessity” might warrant declaring martial law and using military tribunals to try civilians if regular courts are unavailable. footnote26_b3Mp15NDlN4M 26 Milligan, 71 U.S. at 127. Importantly, this latter part of the Court’s opinion is dicta, rather than a necessary and binding part of the Court’s holding. That alone gives reason to doubt whether there is indeed a “necessity” loophole that allows the military to put civilians on trial. But the larger issue is that a necessity exception to the Constitution is impossible: it is a fundamental principle of U.S. constitutional law, reaffirmed countless times both before and after the Milligan ruling, that the government is always constrained by the Constitution, no matter the circumstances. footnote27_dYltouekcT17 27 Youngstown, 343 U.S. 579; Carter v. Carter Coal Company, 298 U.S. 238 (1936); Ex parte Merryman, 17 F. Cas. 144 (C.C.D. Md. 1861); McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1836); and Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137 (1803).

In any event, even if the necessity-based exception articulated in Milligan were considered to be authoritative, it would be extremely narrow. It would allow the military to supplant civilian courts only during an actual war, on “the theatre of active military operations,” where the chaos and fighting are so severe that the regular courts have been forced to close and are unable to operate. footnote28_p3AzgYZxuGtf 28 Milligan, 71 U.S. at 127.

The possibility of using martial law to replace civilian courts with military tribunals should not be confused with the rule established by Ex parte Quirin in 1942. footnote29_oxSsRhaFbNpb 29 Ex parte Quirin, 317 U.S. 1 (1942). Quirin and a handful of more recent Supreme Court decisions related to the U.S. military’s detention facility at Guantanamo Bay allow U.S. citizens not serving in the military to be tried by military commission — a particular type of tribunal used by the U.S. military — if they are “enemy combatants.” footnote30_xqwtmV8T0GfS 30 Quirin, 317 U.S. at 46; Hamdi, 542 U.S. 507; Hamdan, 548 U.S. 557; and Boumediene, 553 U.S. 723. These individuals, the Court has held, are subject to the international law of war. As a result, Congress may authorize their trial by military commission even if civilian courts are open and functioning, pursuant to its authority to “define and punish . . . Offences against the Law of Nations.” footnote31_dSdd4zFSWplH 31 U.S. Const. art. I, § 8 cl. 10. These decisions are not about martial law. They demarcate the line between military and civilian jurisdiction, rather than allowing the military to exercise jurisdiction in an area ordinarily reserved for civilian courts.

Sterling, 287 U.S. at 398; and Duncan, 327 U.S. at 335 (Stone, C. J., concurring in the result). Note that both the portion of Luther that Chief Justice Stone cites and the rest of his opinion directly contradict his own opening proposition.

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952); Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961); Massiah v. United States, 377 U.S. 201 (1964); Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965); Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966); Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 542 U.S. 507 (2004); Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, 548 U.S. 557 (2006); Boumediene v. Bush, 553 U.S. 723 (2008); and War Powers Resolution, 50 U.S.C. §§ 1541–48.

Medellin v. Texas, 552 U.S. 491, 128 S. Ct. 1346, 1350 (2008) (“Justice Jackson’s familiar tripartite scheme provides the accepted framework for evaluating executive action in this area.”); Dames & Moore v. Regan, 453 U.S. 654, 661 (1981) (“Justice Jackson in his concurring opinion in Youngstown . . . brings together as much combination of analysis and common sense as there is in this area.”); and H. Jefferson Powell, The President as Commander in Chief: An Essay in Constitutional Vision (Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2014), 53–135.

18 U.S.C. § 1385; 10 U.S.C. §§ 251–55; 42 U.S.C. § 5121 et seq.; 18 U.S.C. § 4001(a); 10 U.S.C ch. 15, §§ 271–84; and Youngstown, 343 U.S. at 639 (Jackson, J., concurring).

Jennifer K. Elsea, The Posse Comitatus Act and Related Matters: The Use of the Military to Execute Civilian Law, CRS report no. R42659 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2018), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/R42659.pdf. The Posse Comitatus Act nominally allows for constitutional exceptions to its general rule, but none exists.

Hamdan, 548 U.S. at 593n23 (“Whether or not the President has independent power, absent congressional authorization, to convene military commissions, he may not disregard limitations that Congress has, in proper exercise of its own war powers, placed on his powers.”); Youngstown, 343 U.S. at 654–55 (Jackson, J., concurring); Little v. Barreme, 6 U.S. 170 (1804); and Powell, President as Commander in Chief, 101–8.

U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 15 (empowering Congress “[t]o provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions.”); U.S. Const. art. IV, § 4 (“The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government, and shall protect each of them against Invasion; and on Application of the Legislature, or of the Executive (when the Legislature cannot be convened) against domestic Violence.”); and U.S. Const. art. II, § 2, cl. 1 (“The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States.”).

Youngstown, 343 U.S. at 644 (Jackson, J., concurring); and Stephen I. Vladeck, “The Calling Forth Clause and the Domestic Commander-in-Chief,” Cardozo Law Review 29 (January 2008): 1091–108.

Youngstown, 343 U.S. at 643–44 (Jackson, J., concurring); and Powell, President as Commander in Chief, 120–21.

In Justice Jackson’s words, “presidential powers are not fixed but fluctuate, depending upon their disjunction or conjunction with those of Congress.” Youngstown, 343 U.S. at 635 (Jackson, J., concurring); and Powell, President as Commander in Chief, 99–100.

Youngstown, 343 U.S. 579; Carter v. Carter Coal Company, 298 U.S. 238 (1936); Ex parte Merryman, 17 F. Cas. 144 (C.C.D. Md. 1861); McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1836); and Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137 (1803).

No existing federal statute explicitly authorizes the president to declare martial law. footnote1_e2gz0bOSAUhX 1 Two federal statutes (48 U.S.C. §§ 1422, 1591) authorize the territorial governors of Guam and the U.S. Virgin Islands to declare martial law under certain circumstances. Neither statute grants any power to the president. However, there are a number of statutory exceptions to the Posse Comitatus Act that allow the president to deploy the military domestically. footnote2_r1ahbXWK5Fpt 2 Elsea, Posse Comitatus Act, 31–49. The most important of these is the Insurrection Act. footnote3_jqHHW1KF4LVr 3 10 U.S.C. §§ 251–55. Rather than a single package of legislation, the Insurrection Act consists of a series of statutes that were enacted between 1792 and 1871, with a few amendments in the 20th century. footnote4_jXwBEzGKFopP 4 These statutes are the 1792 Calling Forth Act, the 1795 Militia Act, the 1807 Insurrection Act, the 1861 Suppression of the Rebellion Act, and the 1871 Ku Klux Klan Act. The 1792 act and parts of the 1871 act contained sunset provisions, and are no longer in force, but their text and legislative history remain instructive. Vladeck, “Emergency Power and the Militia Acts,” 152n9.

Three of the Insurrection Act’s provisions grant the president power to deploy troops domestically. The first two, Sections 251 and 252, are relatively straightforward and mirror the language of the Calling Forth Clause. Under Section 251, if there is an insurrection in a state, and the state’s legislature (or governor, if the legislature is unavailable) requests federal aid, then the president may deploy the National Guard or the regular armed forces to suppress the insurrection. footnote5_w76CmIbCPwhX 5 10 U.S.C. § 251 (“Whenever there is an insurrection in any State against its government, the President may, upon the request of its legislature or of its governor if the legislature cannot be convened, call into Federal service such of the militia of the other States, in the number requested by that State, and use such of the armed forces, as he considers necessary to suppress the insurrection.”). Section 252 allows the president to deploy troops without a request from the affected state — indeed, even against the state’s wishes — in order to “enforce the laws” of the United States or to “suppress rebellion” whenever “unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages, or rebellion” make it “impracticable” to enforce federal law in that state by the “ordinary course of judicial proceedings.” footnote6_i2k5kdjV2Ytc 6 10 U.S.C. § 252 (“Whenever the President considers that unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages, or rebellion against the authority of the United States, make it impracticable to enforce the laws of the United States in any State by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings, he may call into Federal service such of the militia of any State, and use such of the armed forces, as he considers necessary to enforce those laws or to suppress the rebellion.”).

Nothing in the plain language of Sections 251 and 252 indicates that they authorize martial law. The clause in Section 251 that empowers the military to “suppress an insurrection” does not suggest that federal troops may take over the role of the civilian government in the process. Rather, it contemplates that the military may assist overwhelmed civilian authorities by doing exactly what soldiers are trained to do: fight and defeat an armed and hostile group.

Section 252 suggests a more expansive power: it allows the military to enforce federal law, not just to suppress an insurrection. Nonetheless, it still does not imply that the military may push aside the civilian authorities. In its 1946 decision in Duncan, the Supreme Court made clear that when a statute authorizes the military to encroach on the affairs of civilian government, the Court will interpret it extremely narrowly. If the statute does not specifically say that Congress meant to disrupt the “traditional boundaries” between civilian and military power, the Court will not imply that intent on Congress’s behalf. footnote7_pBNKRAN8WAga 7 Duncan, 327 U.S. at 319–24. Because Section 252 does not expressly authorize the displacement of civilian authorities, it should not be read as license to turn the normal relationship between civilian and military power on its head. Instead, it should be understood merely as authorization for the military to assist civilian government officials when they are overwhelmed by forces attempting to obstruct law enforcement and judicial proceedings.

Section 253 is the only substantive provision of the Insurrection Act that might, on its face, be read to authorize a limited form of martial law. Among other things, it allows the president to use the National Guard or the active duty armed forces to suppress “any insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy” in a state if it “so hinders the execution of [state or federal] laws” that “any part or class of [the state’s] people” is deprived of a constitutional right and “the constituted authorities” of the state “are unable, fail, or refuse to protect” that right. footnote8_naRgZaHGl7eV 8 The full text of 10 U.S.C. § 253 provides the following: The President, by using the militia or the armed forces, or both, or by any other means, shall take such measures as he considers necessary to suppress, in a State, any insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy, if it— (1) so hinders the execution of the laws of that State, and of the United States within the State, that any part or class of its people is deprived of a right, privilege, immunity, or protection named in the Constitution and secured by law, and the constituted authorities of that State are unable, fail, or refuse to protect that right, privilege, or immunity, or to give that protection; or (2) opposes or obstructs the execution of the laws of the United States or impedes the course of justice under those laws. In any situation covered by clause (1), the State shall be considered to have denied the equal protection of the laws secured by the Constitution. As in Section 252, the desires of the state are irrelevant.

By its express terms, Section 253 contemplates a situation in which, rather than needing help from the military to enforce the laws, the civilian authorities are just not enforcing them. As a result, the president may send in troops to suppress whatever insurrection or other violence is causing a portion of the people in that state to be deprived of a constitutional right. Thus, if troops are deployed under Section 253, they will, to some extent at least, take over the role of the civilian government. However, the legislative history of Section 253 indicates that it is best understood as allowing the military to supplant only the local police, and to do so in service of laws duly enacted by civilian authorities. footnote9_n94hMOBzocfz 9 What is now 10 U.S.C. § 253 originated as Section 3 of the 1871 Ku Klux Klan Act. Civil Rights (Ku Klux Klan) Act of 1871, ch. 22, 17 Stat. 13. The act’s legislative history indicates that Congress meant for section 3 to authorize the military to take over the role of the local police, but nothing more. Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 1st Sess. at 567–68 (1871) (statement of Sen. Edmunds). Moreover, the House version of Section 4 of the act explicitly authorized the president to declare martial law, but this language was removed before the bill was sent to the Senate. See Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 1st Sess. at 317 (1871) (statement of Rep. Shellabarger); and Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 1st Sess. at 478 (1871) (statement of Rep. Shellabarger). The fact that Congress considered and removed the martial law language demonstrates that it was aware of martial law and either chose not to authorize it or determined that it lacked the power to do so. This is so narrow that calling it even a “limited form” of martial law would probably be an exaggeration. Indeed, the Department of Defense’s own regulations emphasize the importance of maintaining the “primacy of civilian authority” when troops are deployed in support of law enforcement operations. footnote10_dWuH3RWzcHjv 10 U.S. Department of Defense, “Defense Support of Civilian Law Enforcement Agencies,” Instruction no. 3025.21, last updated February 8, 2019, https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/302521p.pdf; and Ryan Goodman and Steve Vladeck, “The Untold Power of Bill Barr to Direct US Military Forces in Case of ‘Civil Unrest,’” Just Security, June 9, 2020, https://www.justsecurity.org/70672/the-untold-power-of-bill-barr-to-direct-us-military-forces-in-case-of-civil-unrest/.

The Insurrection Act is an exception to the Posse Comitatus Act, but there are also some circumstances in which the latter law simply does not apply. As part V of this report explains, the Posse Comitatus Act does not affect the ability of states to call up their National Guard forces and deploy them within their own borders. In that situation, National Guard troops are operating in State Active Duty status. The Posse Comitatus Act also does not apply when National Guard forces are activated in what is known as Title 32 status, in which the troops remain subject to state command and control, but are used for federal missions and are typically paid for by the federal government. footnote11_dASGI8j6JtO2 11 Elsea, Posse Comitatus Act, 61–62n419; Steve Vladeck, “Why Were Out-of-State National Guard Units in Washington, D.C.? The Justice Department’s Troubling Explanation,” LawFare, June 9, 2020, https://www.lawfareblog.com/why-were-out-state-national-guard-units-washington-dc-justice-departments-troubling-explanation; and Jennifer K. Elsea, The President’s Authority to Use the National Guard or the Armed Forces to Secure the Border, CRS report no. LSB10121 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2018), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/LSB10121.pdf.

On its face, Title 32 appears to authorize a fairly limited set of activities relating to drug interdiction and counter-drug activities, homeland security protection, and training exercises. In early June 2020, however, U.S. Attorney General William Barr put forward a shockingly broad interpretation of the section of Title 32 that addresses “required training and field exercises” for National Guard forces. Under this section, training may include “operations or missions undertaken . . . at the request of the President or Secretary of Defense.” footnote12_x3ef3tAwq155 12 32 U.S.C. § 502(f)(2)(A). In a formal letter explaining the deployment of several states’ National Guard forces to Washington, DC, during protests that followed the police killing of George Floyd in May 2020, Barr asserted that this language allows the president to use the National Guard at any time and for any reason — a reading that effectively creates a gaping loophole in the Posse Comitatus Act. footnote13_mYMc9XBpF66H 13 Kerri Kupec DOJ (@KerriKupecDOJ), “Letter from Attorney General William P. Barr to D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser on the Trump Administration’s restoration of law and order to the District,” Twitter, June 9, 2020, 3:45 p.m., https://twitter.com/kerrikupecdoj/status/1270487263324049410.

The attorney general’s interpretation is suspect for a number of reasons, but even if it were correct, it would not authorize martial law. footnote14_t8Hgw7C31dZD 14 Vladeck, “Why Were Out-of-State National Guard Units in Washington, D.C.?” As with the Insurrection Act, there is no clear statement in Title 32 to suggest that Congress intended to reverse the usual constitutional order in which the military remains subordinate to civilian authority. Under the Supreme Court’s reasoning in Duncan, the language cited by Barr could at most be read to authorize the use of the military to assist civilian law enforcement authorities. footnote15_eNPq2clDL2z1 15 Duncan, 327 U.S. at 319–24.

In short, no existing statute authorizes the president to declare martial law. Congress has given the president considerable authority, however, to use troops domestically to assist in civilian law enforcement activities. Deploying troops under the Insurrection Act might not raise all of the same concerns that would be associated with a declaration of martial law, but there is reason to worry whenever a president uses the military as a domestic police force — particularly without the consent of the state to which the armed forces are sent.

To start, using the military to enforce the law flies in the face of American tradition. The Founders were deeply suspicious of the very idea of a national standing army, believing that it could be used as an instrument of oppression and could pose a threat to the autonomy of the individual states. footnote16_evMWOaBScMhz 16 Vladeck, “Emergency Power and the Militia Acts,” 156. Many of the protections enshrined in the Constitution’s Bill of Rights reflect the hard lessons the Founders learned at the hands of British soldiers about the dangers of allowing the military to act as a domestic police force. They worried that a president equipped with a ready and loyal army would be able to subvert democracy and impose his will on the states and the people.

Moreover, even with the best of intentions, asking the military to stand in for the police can yield disastrous results. Soldiers are trained to fight and destroy an enemy, one that generally lacks constitutional rights. As such, they are poorly suited to performing the duties of police. Forcing them into that role can increase the risk of violence. footnote17_xUF5xdvGdgfv 17 For examples, one need only look to the Kent State massacre in 1970 or incidents during the military deployment to Los Angeles during the 1992 riots. Howard Means, 67 Shots: Kent State and the End of American Innocence (Boston: Da Capo Press, 2016); and Jim Newton, “Did Bill Barr Learn the Wrong Lesson from the L.A. Riots?,” Politico, June 9, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2020/06/09/william-barr-los-angeles-riots-307446. In the words of a Minnesota National Guard member facing deployment in response to the protests that followed the murder of George Floyd: “We’re a combat unit not trained for riot control or safely handling civilians in this context. Soldiers up and down the ranks are scared about hurting someone.” footnote18_oh3gDuZUMZOd 18 Ken Klippenstein, “Exclusive: The Military Is Monitoring Protests in 7 States,” Nation, May 30, 2020, https://www.thenation.com/article/society/national-guard-defense-department-protests/.

Two federal statutes (48 U.S.C. §§ 1422, 1591) authorize the territorial governors of Guam and the U.S. Virgin Islands to declare martial law under certain circumstances. Neither statute grants any power to the president.